Researchers at the University of Adelaide have demonstrated that green hydrogen can be produced reliably using lower-cost, less-purified water, challenging a long-standing assumption that ultra-pure water is a strict requirement for hydrogen electrolysis.

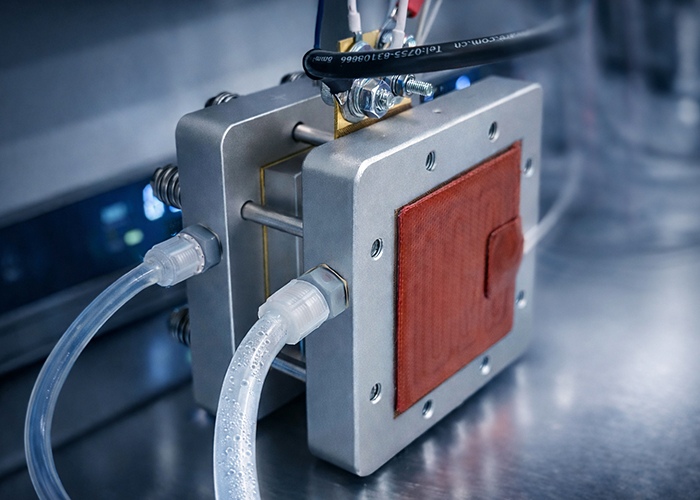

The research team, led by Professor Shi-Zhang Qiao, showed that water treated using reverse osmosis can be used effectively in proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysers without compromising durability or performance. Reverse osmosis is already widely deployed globally, particularly in desalination systems that convert seawater into drinking water.

Traditionally, hydrogen electrolysers rely on highly purified deionised water because even trace amounts of salts and impurities can degrade electrodes and membranes over time. This requirement has added a hidden cost and infrastructure burden to green hydrogen projects, particularly in water-stressed regions where ultra-pure water is expensive or scarce.

By introducing a specially designed anode catalyst, the Adelaide researchers were able to protect the electrolyser from residual impurities left after reverse osmosis treatment. In testing, the system achieved performance comparable to electrolysers operating with ultra-pure deionised water and ran for 2,000 hours without significant degradation.

The findings, published in Nature Catalysis, suggest that water quality constraints may be less of a barrier to hydrogen deployment than previously assumed, provided electrolysers are designed to tolerate real-world conditions.

Professor Qiao said water purity has been an under-examined constraint on the economics of green hydrogen. Reverse osmosis water costs approximately US$0.57 per tonne, compared with around US$9.11 per tonne for deionised water typically used in hydrogen production. While direct use of seawater remains technically challenging, reverse osmosis already delivers large volumes of relatively clean water at scale.

From a smart cities and infrastructure perspective, the research has broader implications. Green hydrogen is increasingly being considered for energy storage, heavy transport, industrial heat and grid balancing. Reducing dependence on ultra-pure water could simplify project design, lower operating costs and make hydrogen production more feasible in coastal and arid urban regions where desalination is already part of the water system.

The work also highlights the growing convergence between water, energy and materials engineering. As cities look to decarbonise critical systems, technologies that reduce interdependencies and resource bottlenecks are likely to play a key role in determining which clean energy pathways scale beyond pilot projects.

While further validation will be required under industrial operating conditions, the results point to a more flexible approach to hydrogen infrastructure — one that aligns more closely with the realities of urban water supply and large-scale deployment.

Image: The electrolyser in action. Photo Hao Liu