Australian National University (ANU) researchers have developed a simple and more cost-efficient method for removing salt from seawater using heat that could address global water shortages.

ANU researchers have developed the world’s first thermal desalination method, in which water remains in the liquid phase throughout the process.

The researchers recently published their findings in Nature Communications. The research demonstrates how the power-saving method is triggered not by electricity but by moderate heat generated directly from sunlight, or waste heat from machines like air conditioners or industrial processes.

“We’re going back to the thermal desalination method but applying a principle that has never been used before, where the driving force and energy behind the process is heat,” said Lead Chief Investigator Dr Juan Felipe Torres.” Thermodiffusion was a phenomenon first reported in detail in the 1850s by Swiss scientist Charles Soret, who experimented with a 30-centimetre water tube where one part of the water was colder and the other hotter. He discovered that the salt ions move slowly to the cold side.”

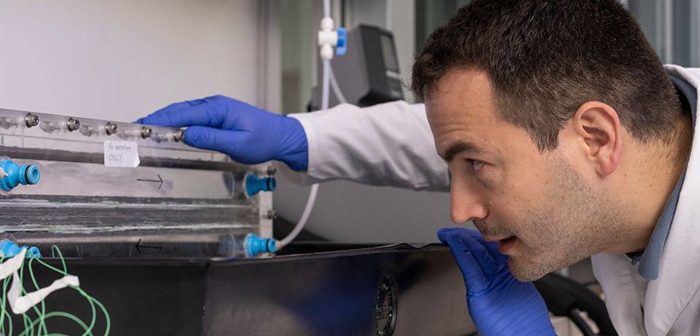

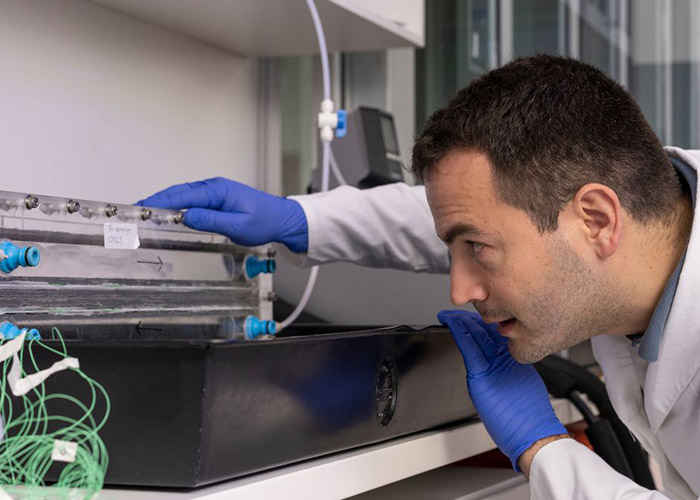

To test whether this effect can be used for water desalination, the ANU researchers pushed seawater through a narrow channel heated from above to 60 degrees and cooled from below to 20 degrees.

“Diffusion was taking 53 days to reach a steady state with a 30-centimetre tube, which is much too long for our purposes and isn’t scalable,” said Torres. “Our mission became to find a way to fast-track the diffusion process. The key was reducing the channel height from 30 centimetres to one millimetre and adding multiple channels.”

Adjusting the conditions for separation could significantly increase the speed of the diffusion process to just a couple of minutes.

Each time the water passed through the channel, its salinity was reduced by 3%, and after repeated cycles, ANU researchers worked out seawater salinity can be reduced from 30,000 parts per million to less than 500.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation says that by 2025, 1.8 billion people will likely face “absolute water scarcity.”

According to the ANU researchers, current desalination technologies, where salt is filtered out via a membrane, require large amounts of electric power and expensive materials that need to be serviced and maintained.

“80% of the world’s desalination methods use reverse osmosis, which adds complexity and is costly to run,” said Torres. “If we continue fine-tuning the current technology without changing the fundamentals, it might not be enough. A paradigm shift is essential to sustain human life over the next century.”

With further testing, the researchers hope to produce the first commercial unit within eight years.

The research has received funding from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Australia’s Science and Technology for Climate Partnership (SciTech4Climate) program. The project also received support from the ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions (ICEDS).